A Heavenly Visitation at Fort Snelling

This is a continuation of the account found in the previous tract titled A Nation Born in a Day.

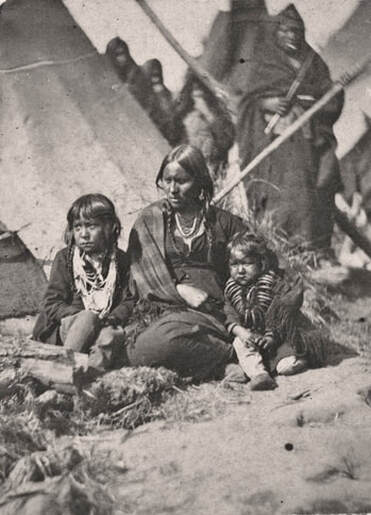

Little Crow’s wife and two children at Fort Snelling prison compound. Among the women, “The ever-present query was, What will become of us, and especially of the men?”

Little Crow’s wife and two children at Fort Snelling prison compound. Among the women, “The ever-present query was, What will become of us, and especially of the men?”

More than a month passed before the court had finished its work. From this point the women and children of the imprisoned men, together with such men as had escaped suspicion, were sent down under a military guard to Fort Snelling, where they, being about fifteen hundred souls, were kept through the winter.

While these events [the spiritual awakening] were transpiring in the prison at Mankato, a very similar work went on in the camp at Fort Snelling. The conditions in both places were a good deal alike. In the camp as well as in the prison they were in trouble and perplexity. In their distresses they were disposed to call upon the Lord. Many of our church members, both men and women, were in the camp. There were Paul, and Simon, and Antoine Renville, the elders of the Hazelwood church, and Joseph Napayshne of the Lower Sioux Agency. But the outlook was as dark to them as it was to us. Mr. J. P. Williamson thus describes the state of the camp in the closing days of 1862:

“The suspense was terrible. The ignorant women had not seen much of the world, and didn’t know anything about law. They, however, knew that their husbands and sons had been murdering the whites, and were now in prison therefor [sic], and they themselves dependent for life on the mercy of the whites. The ever-present query was, What will become of us, and especially of the men? With inquisitive eyes they were always watching the soldiers and other whites who visited them, for an answer, but the curses and threats they received were little understood, except that they meant no good. With what imploring looks have we been besought to tell them their fate. Strange reports were constantly being whispered around the camp. Now, the men were all to be executed, of whom the thirty-eight hanged at Mankato was the first installment, and the women and children scattered and made slaves; now, they were all to be taken to a rocky barren island somewhere, and left with nothing but fish for a support; and, again, they were to be taken away down South, where it was so hot they would all die of fever and ague.”

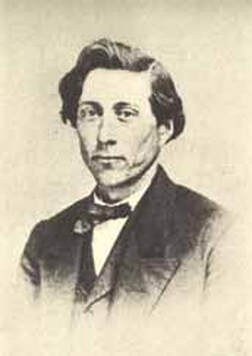

Rev. John P. Williamson, having been providentially absent in Ohio at the time of the outbreak, returned to accompany this camp of despised and hated Dakotas in their journey from the Lower Sioux Agency to Fort Snelling. But it did not immediately appear what he could do for them. “Then he felt such drawing toward the Indian camp that he took the nearest available quarters, and spent the winter ministering temporally and spiritually to this afflicted people.”

When, in the spring following, they were taken down the Mississippi and up the Missouri to Crow Creek, he did not forsake them, but stayed by them in evil and in good report, with the devotion of a lover. Everywhere, and at all times, his thoroughly honest, devoted, and unselfish course commanded the respect and confidence of white men in and out of the army. And his self-abandonment to the temporal and spiritual good of the families of the men in prison begot in them such admiration and confidence that scarcely a prayer was made by them, in all those four years of their imprisonment, without the petition that God would remember and bless “the one who is called John.”

While these events [the spiritual awakening] were transpiring in the prison at Mankato, a very similar work went on in the camp at Fort Snelling. The conditions in both places were a good deal alike. In the camp as well as in the prison they were in trouble and perplexity. In their distresses they were disposed to call upon the Lord. Many of our church members, both men and women, were in the camp. There were Paul, and Simon, and Antoine Renville, the elders of the Hazelwood church, and Joseph Napayshne of the Lower Sioux Agency. But the outlook was as dark to them as it was to us. Mr. J. P. Williamson thus describes the state of the camp in the closing days of 1862:

“The suspense was terrible. The ignorant women had not seen much of the world, and didn’t know anything about law. They, however, knew that their husbands and sons had been murdering the whites, and were now in prison therefor [sic], and they themselves dependent for life on the mercy of the whites. The ever-present query was, What will become of us, and especially of the men? With inquisitive eyes they were always watching the soldiers and other whites who visited them, for an answer, but the curses and threats they received were little understood, except that they meant no good. With what imploring looks have we been besought to tell them their fate. Strange reports were constantly being whispered around the camp. Now, the men were all to be executed, of whom the thirty-eight hanged at Mankato was the first installment, and the women and children scattered and made slaves; now, they were all to be taken to a rocky barren island somewhere, and left with nothing but fish for a support; and, again, they were to be taken away down South, where it was so hot they would all die of fever and ague.”

Rev. John P. Williamson, having been providentially absent in Ohio at the time of the outbreak, returned to accompany this camp of despised and hated Dakotas in their journey from the Lower Sioux Agency to Fort Snelling. But it did not immediately appear what he could do for them. “Then he felt such drawing toward the Indian camp that he took the nearest available quarters, and spent the winter ministering temporally and spiritually to this afflicted people.”

When, in the spring following, they were taken down the Mississippi and up the Missouri to Crow Creek, he did not forsake them, but stayed by them in evil and in good report, with the devotion of a lover. Everywhere, and at all times, his thoroughly honest, devoted, and unselfish course commanded the respect and confidence of white men in and out of the army. And his self-abandonment to the temporal and spiritual good of the families of the men in prison begot in them such admiration and confidence that scarcely a prayer was made by them, in all those four years of their imprisonment, without the petition that God would remember and bless “the one who is called John.”

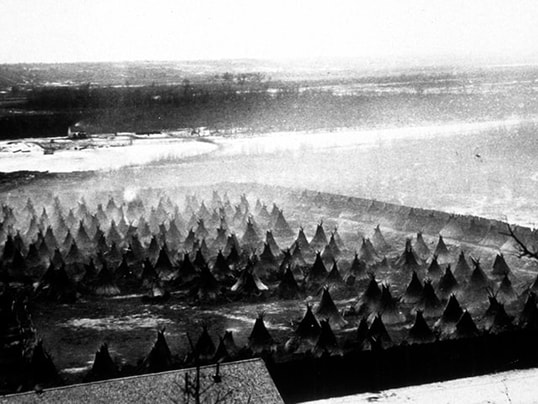

Captured Dakota (Sioux) Indians at Fort Snelling, 1862 or 1863

Captured Dakota (Sioux) Indians at Fort Snelling, 1862 or 1863

The camp at Snelling was on the low ground near the river, where the steamboats were accustomed to land. A high board fence was made around two or three acres of ground, inside of which the Dakotas pitched their cloth tents. In them they cooked and ate and slept, and read the Bible and sang and prayed, and wrote letters to their friends in prison.

By gradual steps, but with overwhelming power, came the heavenly visitation. At first Mr. Williamson used to meet the former members in one of their own teepees. Presently there was an evident softening of hearts. Now news came of the awakening among the prisoners at Mankato. The teepee would not contain half the listeners, so for some time in the middle of winter the meetings were held in the campus, then in a great dark garret over a warehouse, without other fire than spiritual. In that low garret, when hundreds were crouched down among the rafters, only the glistening eyes of some of them visible in the dark, we remember how the silence was sometimes such that the fall of a pin might be heard. Many were convicted; confessions and professions were made; idols treasured for many generations with the highest reverence were thrown away by the score. They had faith no longer in their idols. They laid hold on Christ as their only hope. On this ground they were baptized, over a hundred adults.

It was my privilege to be present frequently, and to see how the good hand of the Lord was upon them in giving them spiritual blessings in their distresses. There was ever a large and active sympathy between the camp and the prison, and frequent letters passed between them. When, at one time, I brought down several hundred letters from the prisoners, and told them of the wonderful work there in progress, it produced a powerful effect. In both camp and prison, both intellectually and spiritually, it was a winter of great advancement.

By gradual steps, but with overwhelming power, came the heavenly visitation. At first Mr. Williamson used to meet the former members in one of their own teepees. Presently there was an evident softening of hearts. Now news came of the awakening among the prisoners at Mankato. The teepee would not contain half the listeners, so for some time in the middle of winter the meetings were held in the campus, then in a great dark garret over a warehouse, without other fire than spiritual. In that low garret, when hundreds were crouched down among the rafters, only the glistening eyes of some of them visible in the dark, we remember how the silence was sometimes such that the fall of a pin might be heard. Many were convicted; confessions and professions were made; idols treasured for many generations with the highest reverence were thrown away by the score. They had faith no longer in their idols. They laid hold on Christ as their only hope. On this ground they were baptized, over a hundred adults.

It was my privilege to be present frequently, and to see how the good hand of the Lord was upon them in giving them spiritual blessings in their distresses. There was ever a large and active sympathy between the camp and the prison, and frequent letters passed between them. When, at one time, I brought down several hundred letters from the prisoners, and told them of the wonderful work there in progress, it produced a powerful effect. In both camp and prison, both intellectually and spiritually, it was a winter of great advancement.

Rev. John P. Williamson, son of missionary Dr. Thomas Williamson

Rev. John P. Williamson, son of missionary Dr. Thomas Williamson

The winter of suspense had worn away, and in the month of April, soon after the Mankato prisoners passed down into Iowa, those at Snelling were placed on a steamboat, and floated down to St. Louis and up the Missouri to Crow Creek, where they were told to make homes. Mr. J. P. Williamson went with them, and remained with them, during those terrible years of suffering and death. Who can tell the story better than he?

“As they look on their native hills for the last time, a dark cloud is crushing their hearts. Down they go to St. Louis, thence up the Missouri to Crow Creek. But this brings little relief, for what of the men; and can the women and children ever live in this parched land, where neither rain nor dew was seen for many weeks?

“The mortality was fearful. The shock, the anxiety, the confinement, the pitiable diet, were naturally followed by sickness. Many died at Fort Snelling. The steamboat trip of over one month, under some circumstances, might have been a benefit to their health, but when 1300 Indians were crowded like slaves on the boiler and hurricane decks of a single boat, and fed on musty hardtack and briny pork, which they had not half a chance to cook, diseases were bred which made fearful havoc during the hot months, and the 1300 souls that were landed at Crow Creek June 1, 1863, decreased to one thousand. For a time a teepee where no one was sick could scarcely be found, and it was a rare day when there was no funeral. So were the hills soon covered with graves.

“Meetings, always an important means of grace, were greatly multiplied. Daily meetings were commenced at Fort Snelling; the steamboat was made a Bethel for daily praise, and the Crow Creek daily prayer-meetings were held each summer under booths, which plan was continued the first summer at Niobrara. Women’s prayer-meetings were commenced at Crow Creek. The children also had meetings, conducted by themselves. All these means were blessed of the Holy Spirit to the breaking of the Herculean chains of Paganism.”

The spring of 1866 saw the prisoners at Davenport released by order of the President; and their families, which had remained at Crow Creek for three dry and parched years, were permitted to join their husbands and brothers and fathers at Niobrara, in the north-east angle of Nebraska. That was a glad and a sad meeting; but the gladness prevailed over the sadness. And now all the Dakotas with whom we had been laboring were again in a somewhat normal condition. All had passed through strange trials and tribulations, and God had brought them out into a large place. The prisoners had prayed that their chains might be removed. God heard them, and the chains were now a thing of the past. They had prayed that they might again have a country, and now they were in the way of receiving that at the hand of the Lord.

“As they look on their native hills for the last time, a dark cloud is crushing their hearts. Down they go to St. Louis, thence up the Missouri to Crow Creek. But this brings little relief, for what of the men; and can the women and children ever live in this parched land, where neither rain nor dew was seen for many weeks?

“The mortality was fearful. The shock, the anxiety, the confinement, the pitiable diet, were naturally followed by sickness. Many died at Fort Snelling. The steamboat trip of over one month, under some circumstances, might have been a benefit to their health, but when 1300 Indians were crowded like slaves on the boiler and hurricane decks of a single boat, and fed on musty hardtack and briny pork, which they had not half a chance to cook, diseases were bred which made fearful havoc during the hot months, and the 1300 souls that were landed at Crow Creek June 1, 1863, decreased to one thousand. For a time a teepee where no one was sick could scarcely be found, and it was a rare day when there was no funeral. So were the hills soon covered with graves.

“Meetings, always an important means of grace, were greatly multiplied. Daily meetings were commenced at Fort Snelling; the steamboat was made a Bethel for daily praise, and the Crow Creek daily prayer-meetings were held each summer under booths, which plan was continued the first summer at Niobrara. Women’s prayer-meetings were commenced at Crow Creek. The children also had meetings, conducted by themselves. All these means were blessed of the Holy Spirit to the breaking of the Herculean chains of Paganism.”

The spring of 1866 saw the prisoners at Davenport released by order of the President; and their families, which had remained at Crow Creek for three dry and parched years, were permitted to join their husbands and brothers and fathers at Niobrara, in the north-east angle of Nebraska. That was a glad and a sad meeting; but the gladness prevailed over the sadness. And now all the Dakotas with whom we had been laboring were again in a somewhat normal condition. All had passed through strange trials and tribulations, and God had brought them out into a large place. The prisoners had prayed that their chains might be removed. God heard them, and the chains were now a thing of the past. They had prayed that they might again have a country, and now they were in the way of receiving that at the hand of the Lord.

Pastor Artemas Ehnamane

Pastor Artemas Ehnamane

For their religious mass-meetings, they had erected a large booth, which served well in the dry weather of summer. Every day, morning and evening, they gathered there for prayer and praise, reading the Bible and telling what God had done for them. They had come too late to plant, and there was but little employment for them, and so the weeks we spent there were weeks of worship, given to the strengthening of the things that remain, and arranging for future educational and Christian work. The churches of the prison and the camp were consolidated, and we selected and licensed Artemas Ehnamane and Titus Ichadooze [Dakota Christians] as probationers for the Gospel ministry.

The multiplication of Dakota readers during the past few years gave a new impulse to our work of translating the Scriptures, and made larger demands for other books. This furnished a great amount of winter work for both Dr. Williamson and myself. In five years we added the Psalms, Ecclesiastes, the Song, and Isaiah, together with the other four books of Moses, to what he had printed in 1865.

The multiplication of Dakota readers during the past few years gave a new impulse to our work of translating the Scriptures, and made larger demands for other books. This furnished a great amount of winter work for both Dr. Williamson and myself. In five years we added the Psalms, Ecclesiastes, the Song, and Isaiah, together with the other four books of Moses, to what he had printed in 1865.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

--Excerpts from Mary and I: Forty Years with the Sioux, Stephen R. Riggs, 1880

Listen here to an audio message which tells more of this glorious awakening after a great massacre.

--Excerpts from Mary and I: Forty Years with the Sioux, Stephen R. Riggs, 1880

Listen here to an audio message which tells more of this glorious awakening after a great massacre.