A Nation Born in a Day

Stephen Riggs, author of the following account, was a missionary to the Sioux (Dakota) in Minnesota at the time of the Sioux Uprising of 1862 in which nearly 650 settlers—men, women, and children--and over 100 soldiers were killed.

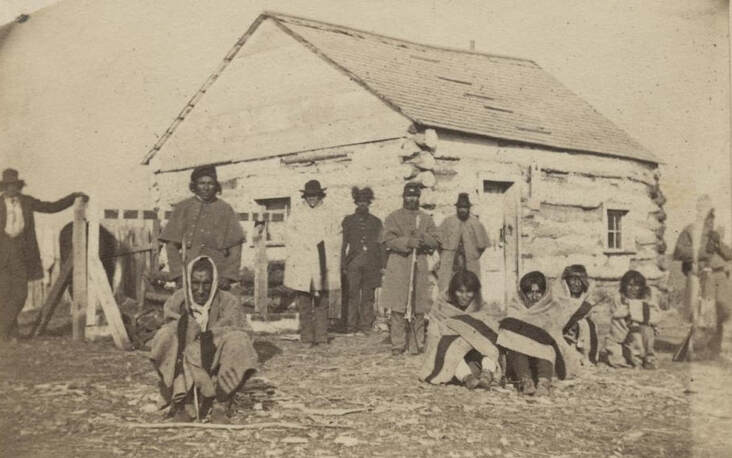

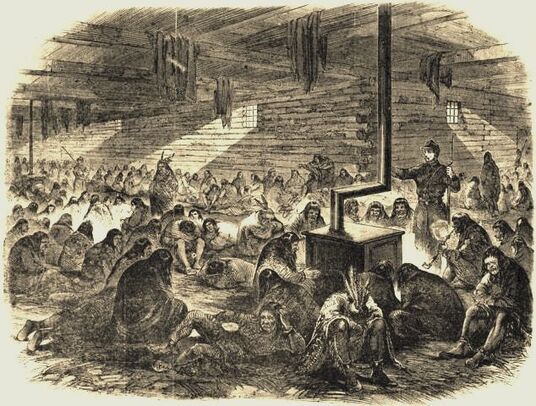

Prison scene

Prison scene

Naturally, we supposed that men who knew themselves guilty would have fled to Manitoba with Little Crow. The greater number of such men had undoubtedly gone. But some were found remaining who had participated in individual murders, some who had abused white women, and more who had been mixed up in the various raids made upon the white settlements. [These] men were placed in confinement to await the ordeal of a trial.

In a few weeks, instead of taking individuals for trial against whom some specific charge could be brought, the plan was adopted to subject all the grown men, with a few exceptions, to an investigation of the commission, trusting that the innocent could make their innocency appear. Of nearly four hundred cases which came before the commission, only about fifty were cleared, twenty were sentenced to imprisonment, and more than three hundred were condemned to be hanged. The greater part of these were condemned on general principles, without any specific charges proved.

More than a month passed before the court had finished its work. It remained now to go into winter-quarters, to guard the prisoners, and to await such orders as should come from the President. It was November when the camp was removed from the Lower Sioux Agency to Mankato.

On receiving the papers transmitted from the military commission, President Lincoln had placed them in the hands of impartial men, with instructions to report the cases which, according to the testimony, were convicted of participation in individual murders or in violating white women. Acting under these instructions, thirty-nine cases were reported, and these were ordered by the President to be executed [the rest being reprieved].

The separation was effected on Monday morning, the men to be executed being taken from the log jail, in which all were confined, to an adjoining stone building, where they were additionally secured by being chained to the floor. Colonel Miller then informed them of the order of the President that they should be hanged on the Thursday following, and they were advised to prepare themselves for that event.

In a few weeks, instead of taking individuals for trial against whom some specific charge could be brought, the plan was adopted to subject all the grown men, with a few exceptions, to an investigation of the commission, trusting that the innocent could make their innocency appear. Of nearly four hundred cases which came before the commission, only about fifty were cleared, twenty were sentenced to imprisonment, and more than three hundred were condemned to be hanged. The greater part of these were condemned on general principles, without any specific charges proved.

More than a month passed before the court had finished its work. It remained now to go into winter-quarters, to guard the prisoners, and to await such orders as should come from the President. It was November when the camp was removed from the Lower Sioux Agency to Mankato.

On receiving the papers transmitted from the military commission, President Lincoln had placed them in the hands of impartial men, with instructions to report the cases which, according to the testimony, were convicted of participation in individual murders or in violating white women. Acting under these instructions, thirty-nine cases were reported, and these were ordered by the President to be executed [the rest being reprieved].

The separation was effected on Monday morning, the men to be executed being taken from the log jail, in which all were confined, to an adjoining stone building, where they were additionally secured by being chained to the floor. Colonel Miller then informed them of the order of the President that they should be hanged on the Thursday following, and they were advised to prepare themselves for that event.

Some days before this, Dr. [Thomas] Williamson had baptized Round Wind, who was reprieved by an order from the President, which came only a day or so before the executions, reducing the number to thirty-eight.

The executions took place. The other prisoners, through crevices in the walls of their log prison-house, saw them hanged. And they were deeply affected by it, albeit they did not show their feelings as white men would have done under like circumstances.

At the close of the week, Dr. Williamson, finding himself quite worn out with abundant labors, returned to St. Peter to rest in his family. The Sabbath morning came. The night before, a fresh snow had fallen nearly a foot deep. Colonel Miller thought it was only humane to let the prisoners go out into the yard on that day, to breathe the fresh air. And so it was we gathered in the middle of that enclosure, and all that company of chained men stood while we sang hymns and prayed and talked of God’s plan of saving men from death. To say that they listened with attention and interest would not convey the whole truth. Evidently, their fears were thoroughly aroused, and they were eager to find out some way by which the death they apprehended could be averted. This was their attitude. It was a good time to talk to them of sin—to tell them of their sins. It was a good time to unfold to them God’s plan of saving from sin—to tell them God’s own son, Jesus Christ our Lord, died to save them from their sins, if they would only believe. A marvelous work of grace was already commencing in the prison.

The next day after the Sabbath I left Mankato, and returned to my family in St. Anthony, where I spent the remaining part of the winter, partly in preparing school-books, for which there arose a sudden demand, and all we had on hand were destroyed in the outbreak; and partly in helping on the spiritual and educational work in the camp at Fort Snelling. But Dr. Williamson, living as he did in St. Peter, gave his time during the winter to teaching and preaching to the men in the prison. Immediately on their reaching Mankato, he and his sister came up to visit them, and were glad to find them ready to listen.

The prisoners asked for books. Only two copies of the New Testament and two or three copies of the Dakota hymn-book were found in prison. Some of each were obtained elsewhere, and afterward furnished them, but not nearly as many as they needed. Some slates and pencils and writing paper were provided for them. And still later in the winter some Dakota books were given them. From this time on the prison became a school, and continued to be such all through their imprisonment. They were all exceedingly anxious to learn. And the more their minds were turned toward God and his Word, the more interested they became in learning to read and write. In their minds, books and the religion we preached went together.

Soon after this first visit of Dr. Williamson, they began to sing and pray publicly, every morning and evening; which they continued to do all the while they were in prison. This they commenced of their own accord.

Before the executions, Robert Hopkins, who was, at that time, the leader in all that pertained to worship, handed to Dr. Williamson the names of thirty men who had then led in public prayer. And not very long after, sixty more names were added to the list of praying ones. This was regarded by themselves very much in the light of making a profession of religion.

In a few weeks a deep and abiding concern for themselves was manifest. Here were hundreds of men who had all their life refused to listen to the Gospel. They now wanted to hear it. There was a like number of men who had refused to learn to read. Now almost all were eager to learn. And along with this wonderful awakening on the subject of education sprang up the more marvelous one of their seeking after God—some god. Their own gods had failed them signally, as was manifest by their present condition. Their conjurers, their medicine-men, their makers of wakan, were nonplussed. Even the women taunted them by saying, “You boasted great power as wakan men; where is it now?” These barriers, which had been impregnable and impenetrable in the past, were suddenly broken down. Their ancestral religion had departed. They were unwilling now, in their distresses, to be without God—without hope, without faith in something or some one. Their hearts were aching after some spiritual revelation.

Then, if human judgment resulted in what they had seen and realized, what would be the results of God’s judgment? There was such a thing as sin, and there was such a person as Christ, God’s Son, who is a Saviour from sin. These impressions were made by the preaching of the Word. These impressions became convictions. The work of God’s Spirit had now commenced among them, and it was continued all winter, “deep and powerful, but very quiet,” as one wrote.

Some of these men, in their younger days, had heard the Messrs. Pond [brothers Samuel and Gideon] talk of the white man’s religion. They were desirous now, in their trouble, to hear from their old friends, whose counsel they had so long rejected. To this request, Mr. G. H. Pond responded, and spent some days in the prison, assisting Dr. Williamson. Rev. Mr. Hicks, pastor of the Presbyterian church in Mankato, was also taken into their counsels and gave them aid. For several weeks previous, many men had been wishing to be baptized, and thus recognized as believers in the Lord Jesus Christ. This number increased from day to day, until about three hundred—just how many could not afterward be ascertained—stood up and were baptized into the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. The circumstances were peculiar, the whole movement was marvelous, it was like a “nation born in a day.” The brethren desired to be divinely guided; and, after many years of testing have elapsed, we all say that was a genuine work of God’s Holy Spirit.

Several weeks after the events above described, in the month of March, I went up to Mankato and spent two Sabbaths with the men in prison; and while there labored to establish them in their new faith, and at the close of my visit, by the request of Dr. Williamson, I administered to these new converts the Lord’s Supper. Robert Hopkins and Peter Big Fire, with others who were soon brought to the front, became the leaders and exponents of Christian faith among the prisoners.

This first communion in the prison made a deep impression upon myself. It began to throw light upon the perplexing questions that had started in my own mind, as to the moral meaning of the outbreak. God’s thought of it was not my thought. As the heavens were higher than the earth, so his thoughts were higher than mine. I accepted the present interpretation of the events, and thanked God and took courage.

The Indians had not meant it so. In their thought and determination, the outbreak was the culmination of their hatred of Christianity. But God, who sits on the throne, had made it result in their submission to him. This was marvelous in our eyes.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

--Excerpts from Mary and I: Forty Years with the Sioux, Stephen R. Riggs, 1880

Listen here to an audio message which tells more of this glorious awakening after a great massacre.

The executions took place. The other prisoners, through crevices in the walls of their log prison-house, saw them hanged. And they were deeply affected by it, albeit they did not show their feelings as white men would have done under like circumstances.

At the close of the week, Dr. Williamson, finding himself quite worn out with abundant labors, returned to St. Peter to rest in his family. The Sabbath morning came. The night before, a fresh snow had fallen nearly a foot deep. Colonel Miller thought it was only humane to let the prisoners go out into the yard on that day, to breathe the fresh air. And so it was we gathered in the middle of that enclosure, and all that company of chained men stood while we sang hymns and prayed and talked of God’s plan of saving men from death. To say that they listened with attention and interest would not convey the whole truth. Evidently, their fears were thoroughly aroused, and they were eager to find out some way by which the death they apprehended could be averted. This was their attitude. It was a good time to talk to them of sin—to tell them of their sins. It was a good time to unfold to them God’s plan of saving from sin—to tell them God’s own son, Jesus Christ our Lord, died to save them from their sins, if they would only believe. A marvelous work of grace was already commencing in the prison.

The next day after the Sabbath I left Mankato, and returned to my family in St. Anthony, where I spent the remaining part of the winter, partly in preparing school-books, for which there arose a sudden demand, and all we had on hand were destroyed in the outbreak; and partly in helping on the spiritual and educational work in the camp at Fort Snelling. But Dr. Williamson, living as he did in St. Peter, gave his time during the winter to teaching and preaching to the men in the prison. Immediately on their reaching Mankato, he and his sister came up to visit them, and were glad to find them ready to listen.

The prisoners asked for books. Only two copies of the New Testament and two or three copies of the Dakota hymn-book were found in prison. Some of each were obtained elsewhere, and afterward furnished them, but not nearly as many as they needed. Some slates and pencils and writing paper were provided for them. And still later in the winter some Dakota books were given them. From this time on the prison became a school, and continued to be such all through their imprisonment. They were all exceedingly anxious to learn. And the more their minds were turned toward God and his Word, the more interested they became in learning to read and write. In their minds, books and the religion we preached went together.

Soon after this first visit of Dr. Williamson, they began to sing and pray publicly, every morning and evening; which they continued to do all the while they were in prison. This they commenced of their own accord.

Before the executions, Robert Hopkins, who was, at that time, the leader in all that pertained to worship, handed to Dr. Williamson the names of thirty men who had then led in public prayer. And not very long after, sixty more names were added to the list of praying ones. This was regarded by themselves very much in the light of making a profession of religion.

In a few weeks a deep and abiding concern for themselves was manifest. Here were hundreds of men who had all their life refused to listen to the Gospel. They now wanted to hear it. There was a like number of men who had refused to learn to read. Now almost all were eager to learn. And along with this wonderful awakening on the subject of education sprang up the more marvelous one of their seeking after God—some god. Their own gods had failed them signally, as was manifest by their present condition. Their conjurers, their medicine-men, their makers of wakan, were nonplussed. Even the women taunted them by saying, “You boasted great power as wakan men; where is it now?” These barriers, which had been impregnable and impenetrable in the past, were suddenly broken down. Their ancestral religion had departed. They were unwilling now, in their distresses, to be without God—without hope, without faith in something or some one. Their hearts were aching after some spiritual revelation.

Then, if human judgment resulted in what they had seen and realized, what would be the results of God’s judgment? There was such a thing as sin, and there was such a person as Christ, God’s Son, who is a Saviour from sin. These impressions were made by the preaching of the Word. These impressions became convictions. The work of God’s Spirit had now commenced among them, and it was continued all winter, “deep and powerful, but very quiet,” as one wrote.

Some of these men, in their younger days, had heard the Messrs. Pond [brothers Samuel and Gideon] talk of the white man’s religion. They were desirous now, in their trouble, to hear from their old friends, whose counsel they had so long rejected. To this request, Mr. G. H. Pond responded, and spent some days in the prison, assisting Dr. Williamson. Rev. Mr. Hicks, pastor of the Presbyterian church in Mankato, was also taken into their counsels and gave them aid. For several weeks previous, many men had been wishing to be baptized, and thus recognized as believers in the Lord Jesus Christ. This number increased from day to day, until about three hundred—just how many could not afterward be ascertained—stood up and were baptized into the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. The circumstances were peculiar, the whole movement was marvelous, it was like a “nation born in a day.” The brethren desired to be divinely guided; and, after many years of testing have elapsed, we all say that was a genuine work of God’s Holy Spirit.

Several weeks after the events above described, in the month of March, I went up to Mankato and spent two Sabbaths with the men in prison; and while there labored to establish them in their new faith, and at the close of my visit, by the request of Dr. Williamson, I administered to these new converts the Lord’s Supper. Robert Hopkins and Peter Big Fire, with others who were soon brought to the front, became the leaders and exponents of Christian faith among the prisoners.

This first communion in the prison made a deep impression upon myself. It began to throw light upon the perplexing questions that had started in my own mind, as to the moral meaning of the outbreak. God’s thought of it was not my thought. As the heavens were higher than the earth, so his thoughts were higher than mine. I accepted the present interpretation of the events, and thanked God and took courage.

The Indians had not meant it so. In their thought and determination, the outbreak was the culmination of their hatred of Christianity. But God, who sits on the throne, had made it result in their submission to him. This was marvelous in our eyes.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

--Excerpts from Mary and I: Forty Years with the Sioux, Stephen R. Riggs, 1880

Listen here to an audio message which tells more of this glorious awakening after a great massacre.